References

1. Rello,L., Baeze-Yates, R., Dempere-Marco, L., & Saggion, H. (2013). Frequent Words Improve Readability and Short Words Improve Understandability for People with Dyslexia. In Proceeding of INTERACT'13, ser Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Kotz, P., Marsden, G., Lindgaard, G., Wesson, J., & Winckler, M Eds. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013, vol. 8120, 203-219. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-40498-6_15

2. Lesley Xie, Alissa N. Antle, and Nima Motamedi. 2008. Are tangibles more fun?: comparing children's enjoyment and engagement using physical, graphical and tangible user interfaces. In Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on Tangible and embedded interaction (TEI '08). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 191-198. DOI=http://dx.doi.org.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/10.1145/1347390.1347433

3. Alissa N. Antle, Milena Droumeva, and Daniel Ha. 2009. Hands on what?: comparing children's mouse-based and tangible-based interaction. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children (IDC '09). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 80-88. DOI: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/10.1145/1551788.1551803

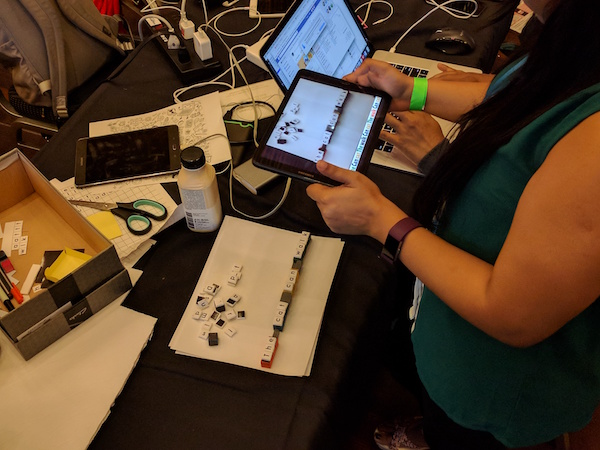

4. Fan, M., Antle, A.N., Hoskyn, M. Neustaedter, C. and Cramer, E.S. 2017. Why tangibility matters: A design case study of at-risk children learning to read and spell. In Proceedings of Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '17), 1805-1816.

5. Antle, A.N. Fan, M., and Cramer. E.S. PhonoBlocks: A tangible system for supporting dyslexic children learning to read. In Proceedings Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (TEI '15), ACM Press (Stanford, CA, USA, January 16-19), 533-538.

6. Antle, A.N. and Wise, A.F. 2013. Getting down to details: Using theories of cognition and learning to inform tangible user interface design, Interacting with Computers 25(1), 1-20. DOI: 10.1093/iwc/iws007

7. Fan, M., Antle, A.N. and Cramer, E.S. 2016. Design rationale: Opportunities and recommendations for tangible reading systems for children, In Proceedings of Conference on Interaction Design for Children (IDC '16), 101-112.

8. Hines, S. J. (2009). The Effectiveness of a Color-Coded, Onset-Rime Decoding Intervention with First-Grade Students at Serious Risk for Reading Disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 24(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5826.2008.01274.x

9. Cramer, E.S., Antle, A.N. and Fan, M. 2016. The code of many colours: Evaluating the effects of a dynamic colour-coding scheme on children's spelling in a tangible software system. In Proceedings of Conference on Interaction Design for Children (IDC '16), 473-485.

10. Berninger, V. W., Abbott, R. D., Zook, D., Ogier, S., Lemos-Britton, Z., & Brooksher, R. (1999). Early Intervention for Reading Disabilities Teaching the Alphabet Principle in a Connectionist Framework. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 32(6), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/002221949903200604

11. Kelly, K., & Phillips, S. (2011). Teaching Literacy to Learners with Dyslexia: A Multi-sensory Approach. London: SAGE